Tests that are considered proven for diagnosing food allergy have been skin tests, blood tests that look for IgE (the class of antibody associated with allergic diseases) and, if necessary, an office ingestion challenge. When the skin tests and blood tests are normal, the scientific conventional approach is to call a recurrent specific food reaction an intolerance. Both the allergist and patient feel less than satisfied when the explanation is not well-defined.

Tests that are considered proven for diagnosing food allergy have been skin tests, blood tests that look for IgE (the class of antibody associated with allergic diseases) and, if necessary, an office ingestion challenge. When the skin tests and blood tests are normal, the scientific conventional approach is to call a recurrent specific food reaction an intolerance. Both the allergist and patient feel less than satisfied when the explanation is not well-defined.

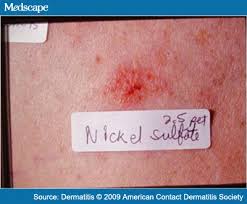

Another explanation, though, has been proposed that is not widely recognized but utilizes a well-accepted diagnostic method. The medical literature reports that allergens considered to be causes of contact (i.e. external exposure to a chemical only on the top of the skin) dermatitis can also trigger skin symptoms when they are ingested. This mechanism is reported almost entirely in dermatology journals and in primarily non-American ones. The method used for diagnosis is the patch test, in which a compound is placed on some type of adhesive paper and taped to the back for 48 hours. If the person reacts, there will be a raised area with surrounding redness after the patch is removed. The area may not become reactive for another 24-48 hours after the patch is removed. Consequently, this testing method requires three office visits during a week.

The most common contact allergen mentioned in the literature to cause skin symptoms when ingested is nickel. Nickel is present in trace amounts in numerous foods. However, nickel is considered to be in relatively high amounts in beans, lentils, shellfish, chocolate, coffee, spinach and soy—even though conventional skin and blood tests for such foods are normal. A point-based low-nickel scoring diet was proposed in 2013 as a treatment

The other two most common contact allergens identified with foods—based on a 2008 retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data base—are balsam of Peru and propylene glycol. In a 2014 review article of systemic contact dermatitis to foods, patients who react to balsam of Peru on patch tests are told to specifically avoid citrus fruits, tomatoes, liquors and spices such as cinnamon, vanilla, cloves and ginger. Propylene glycol is very commonly used as a thickening agent in foods such as dressings, baked goods and beverages.

Systemic nickel hypersensitivity as a cause of gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms is still considered to be controversial. In a 2011 article in European Annals of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the author wrote that the data in the literature are not conclusive and studies lack clear first-hand evidence. Four years later, a review of the topic in the same journal concluded that a subset of patients with contact sensitization to nickel may benefit from dietary avoidance of oral nickel. Last year, a pilot study from the University of Tokyo of 147 patients with irritable bowel syndrome and 22 healthy controls concluded that there was a statistically significant difference in hypersensitivity to nickel and to zinc on a test tube study of lymphocytes. Another publication last year reported that some patients with allergic contact dermatitis from either balsam of Peru or nickel improved on the biologic dupilimab (brand name Dupixent) without needing to continue a strict avoidance diet.

We all crave certainty and accuracy in our lives. Despite this year’s numerical designation, the first half of it has been far from 20/20 foresight. We’ve seen that we can be susceptible to preconceived notions that certain events cannot happen. As we recognize and adapt to the changes of this year, we will also need to be open-minded about ways in which allergic diseases can happen when the theoretical can be supported by well-founded basic and clinical research.

Dr. Klein